Under your skin anatomical flap books

25 Oct 2019

Susan Isaac

Anatomical flap books were being used to show what’s hidden under our skin as early as the 1500s. They take their name from the layers of movable paper flaps that are lifted to reveal the layers below, making the viewer an active participant who ‘dissects’ the body by opening the flaps.

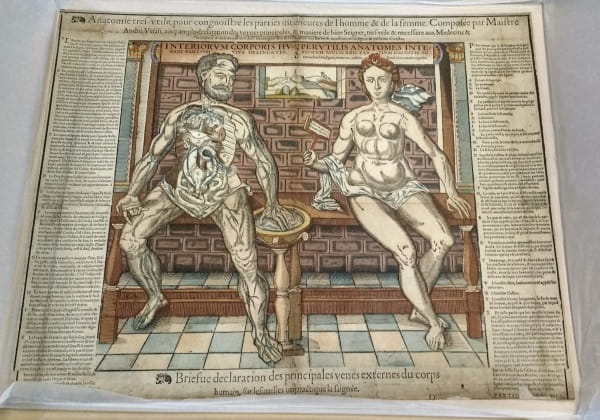

Early examples were known as fugitive sheets and designed to show the internal organs and structures under the skin. Prints like this were often damaged or lost, which led to the description ‘fugitive’ sheet. Anatomie très utile: ‘The anatyme of the inwarde partis of man and woman’ (c.1559) is an example of an anatomy print with multiple liftable flaps that reveal the interior organs of a naked man and woman seated beside each other. The illustration is a woodcut with hand-colouring and the woman holds a sign with the motto “Nosce te ipsum. Knowe thyself”.

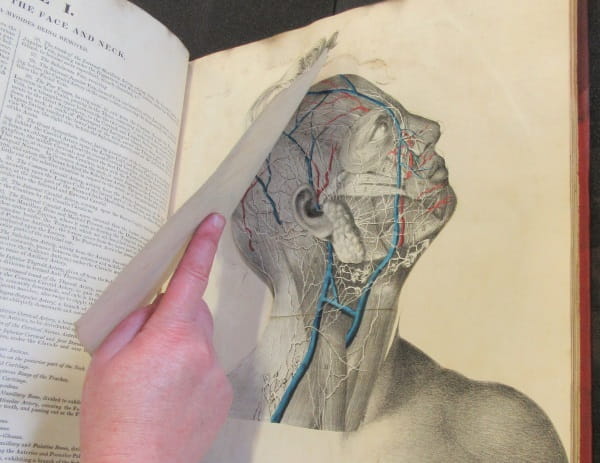

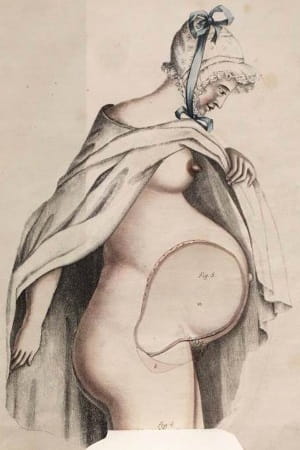

New printing techniques introduced in the nineteenth century, made it easier for publishers to produce detailed colour illustrations. Edward William Tuson, a surgeon who taught anatomy, published his great work Myology in 1828. His book is very technical and rich in detail, using hand-coloured lithograph images with multiple pieces representing veins and muscles. This image is taken from his Supplement to Myology: containing the arteries, veins, nerves, and lymphatics of the human body (1828).

As the century progressed, new technologies were developed and publishing costs continued to decease, while the market to popularise science and medicine expanded. Gustav Witkowski created the Moveable Atlas of the Human Body (1876) using double-sided printing and die-cutting techniques to give us an entire human body in flaps. He made full use of the available technology to show the structure of the human body, using both the simplistic flap of single pages folded together, as well as intricate pieces that lock together to ‘pop up’ as the reader opens the various flaps. They're beautiful and imaginative, with different kinds of paper and shapes used to represent the complexities of the anatomy. The atlas was published as an eleven volume series, originally in French. These volumes are delicate and are in need of conservation now. You can find out how you can help us to preserve these items here.

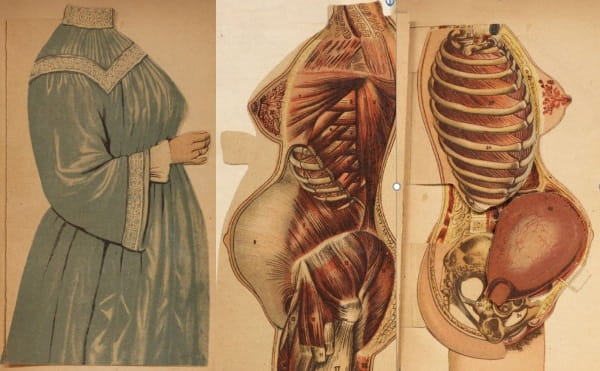

As this mass market developed to educate the public, flap anatomies were incorporated into ‘home health manuals’. These later images often had an additional top layer showing a more demure, fully-clothed figure as shown by this example from Woman in girlhood, wifehood, motherhood by Myer Solis-Cohen (1906). The book aimed to provide information on a woman’s responsibilities and duties throughout her life and be a guide to the maintenance of her health and that of her children.

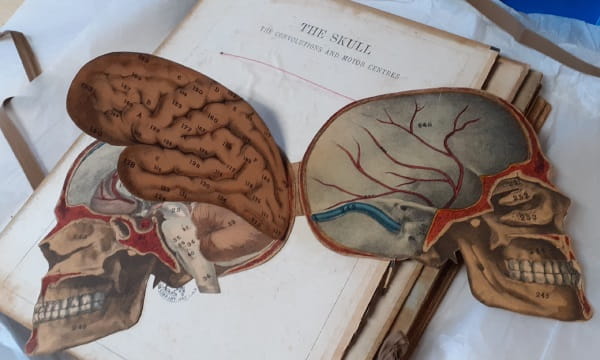

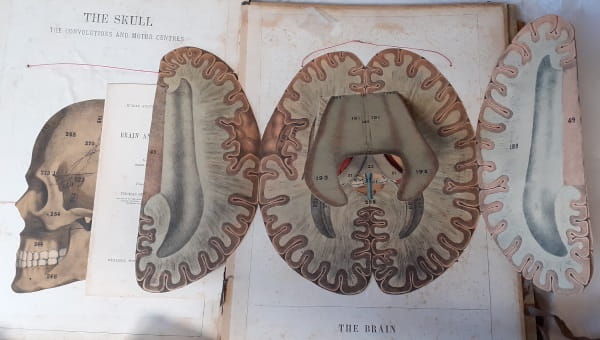

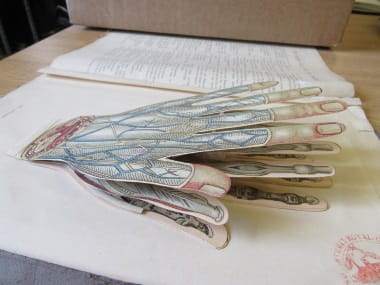

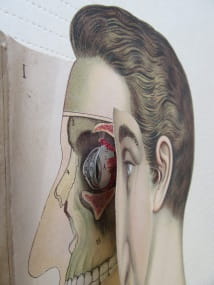

My last example of an anatomical flap book comes from the same period. The household physician, by John McGregor-Robertson (1907), is a guide to the preservation of health and the domestic treatment of illness, which was reprinted several times. It covered everything from a detailed description of the human body, with pop-up anatomical diagrams, to pregnancy, via cookery for invalids and how to live a healthy lifestyle. These illustrations are taken from The household physician: Dissected models of the human head and the human hand, showing the internal structure.

It is fascinating to trace the development of the flap book genre, beginning with early examples from the sixteenth century, to the colourful “golden age” of complex flaps in the nineteenth century. Once used by professionals for educational purposes, pop-up books are nowadays generally designed for children. However, these books are still wonderful objects showing you what’s under your skin.

Susan Isaac, Information Services Manager