Lifelike model of child’s skull and brain created using 3D printing, heralding breakthrough in surgical training

21 Nov 2016

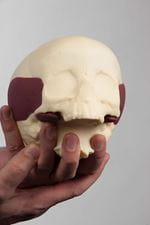

Experts at the Royal College of Surgeons have used 3D printing and advanced modelling techniques to create a realistic model of a toddler’s skull and brain, heralding a breakthrough in the training of neurosurgeons.

The model head, which is the first of its kind, mimics the delicate texture and weight of a child’s skull. The brain has been designed to simulate the dimensions, feel and consistency of an infant’s.

Surgeons in training often practise operations on human cadavers which have been donated by members of the public before they die. However, child cadavers are not available for paediatric surgeons, or surgeons in training to use, so they practise on adult cadavers or models.

Trainees will be able to use the portable model paediatric heads to become skilled at a paediatric neurosurgery operation, before performing it for the first time. They will also be able to use it in the operating theatre, before an operation, to become familiar with a procedure and the correct instruments, under the supervision of their consultant surgeon trainer.

The design team at the RCS took a computerised tomography (CT) scan of a toddler’s skull using high definition CT scanning equipment at the Natural History Museum. The skull, which dates back to the 1800s, is in the RCS’s medical museum. This scan was then used to create a 3D printed model with full anatomical detail. From this, they created the “babyMARTYN”, infant, skulls.

The skull is made from polyurethane resin, while a gelatin-based substance has been used to create a realistic brain, lifelike muscles have been made from silicone and plastic was used to make the dura – the membrane which surrounds the brain.

The models have been named the “babyMARTYN” after Mr Martyn Cooke, Head of Conservation at the RCS, who developed the models with a team of surgeons and a sculptor.

Mr Cooke said: “These models signal a breakthrough in the way we train surgeons who operate on very small children.For the first time, they will have an opportunity to practise on a realistic, 3D model of an infant’s skull and brain which has a simulated tumour, blood clot, or fluid on the brain. This will help surgeons to become more adept at using the equipment as well as more confident and experienced in their job. These models should ultimately help to improve the care that children in hospitals across the country receive.

“At the RCS, we are committed to investing in improving surgical training and advancing patient care and are very excited by this latest technological development.”

Mr Cooke developed the models after Major David Baxter - a trainee neurosurgeon in the Royal Army Medical Corps - asked the RCS to create a model of the brain and skull for surgeons to practise treating adults with head trauma injuries. Mr Cooke successfully designed the adult models after experimenting with waxes, resin and gelatin.

Miss Mary Murphy, a consultant neurosurgeon at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, suggested it would be useful to develop an infant head model. This was done collaboratively with Mr Cooke, Miss Murphy, Miss Claudia Craven - a Neurosurgery Trainee, and Ms Clare Rangeley – a Sculptor and Medical Model Maker.

Additional quotes

Consultant neurosurgeon Miss Murphy, who is Deputy Clinical Director at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, said:

“There are a number of adult models of the head available, but to our knowledge, this is the only infant head model in the world which can be used to practise multiple operations.

“Clearly, it is of paramount importance that trainees have an opportunity to perfect an operation in a simulated environment before performing it for the first time on a child, if this is at all possible.”

Ms Rangeley said: “My brief was to design a model of an 18-month-old child’s skull with a brain tumour and fluid on the brain. Using the 3D print of a skull enabled us to make it very realistic. I was surprised to learn that a toddler’s skull is paper thin in parts - so it’s important for surgeons to experience drilling into different sections so they know how much pressure to apply.

“The brain needed to feel like the human equivalent so that trainee surgeons could practise techniques to alleviate excess fluid on the brain. It was also important that the cerebellum (or base of the brain) and the tumour or blood clot within it, look and feel very realistic, so that the trainee surgeons can identify the various structures and assess how they would proceed in a simulated operation.”

Miss Craven said: “Performing surgery on a baby or toddler is much more high risk because if they lose even a few milliletres of blood it can make a huge difference to their outcomes.

“Rehearsal for complex or high-risk procedures is important in any field of medicine, particularly surgery. We learn in a supported environment in the operating theatre and we often supplement that learning by attending courses, or practising on cadavers.

“There is no child cadaveric material available for surgeons to practise on, in the same way as there is for adults. These very realistic models fill this niche. The models have bespoke anatomy and they are portable, so you could use them in the operating theatre to familiarise yourself with a procedure before an operation, or use them to practise a surgical technique around the kitchen table at home.”

Notes to editors

- Mr Martyn Cooke is Head of the Conservation Unit at the Royal College of Surgeons. He is a trained histologist and prepared patients’ biopsies for medical analysis. He has also had a life-long interest in making models. Mr Cooke combined his two interests in life to design a model skull and brain. This is used by neurosurgeons to practise treating patients who have suffered a head trauma, or to practise removing a brain tumour.

- Miss Mary Murphy is a Consultant Neurosurgeon at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in Queen’s Square, London. She is Deputy Clinical Director of Neurosurgery at the hospital and a former neurosurgery tutor at the Royal College of Surgeons (2010-2013).

- Miss Claudia Craven is a third year Neurosurgery Trainee based in the North Thames region, so she rotates between working at The National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in Queen’s Square, and the Royal London Hospital.

- Clare Rangeley is a Sculptor and Medical Model Maker. Based near Bristol, she has been a sculptor for over 30 years and making medical models for over 20 years.

- The acronym MARTYN stands for: Model Anatomical Replica for Training Young Surgeons.

- The Royal College of Surgeons of England is a professional membership organisation and registered charity, which exists to advance surgical standards and improve patient care.

- For more information, please contact the Press Office:

- Telephone: 020 7869 6047/6052

- Email: pressoffice@rcseng.ac.uk

- Out of hours media enquiries: 07966 486832