Sir Harold Gillies’ Patient Case Files, 1915-1925. (RCSEng Archives Ref. MS0513)

02 Nov 2020

Victoria Rea

When Sam Mendes collected the Golden Globe for Best Director for the film 1917, he dedicated the award to his grandfather, Alfred. “He signed up for the First World War aged 17. I hope he’s looking down on us. And I fervently hope it never, ever happens again.”

Sir Harold Gillies’ Patient Case Files, which are held in the Royal College of Surgeons of England Archives, elicit the same response. They contain photographs, clinical notes, watercolours and x-rays relating to over 2,500 soldiers who underwent facial reconstruction surgery at the centre set up by Gillies at Queen Mary’s Hospital, Sidcup, during the First World War. The files contribute to learning about surgery, military history, art and social history, making them a good example of the multi-disciplinary strength of the RCSEng archive collections.

Harold Gillies, FRCS (1882-1960) is widely considered to be the father of modern plastic surgery. Born in New Zealand, Gillies trained in England and joined the Army Medical Corps at the outbreak of war. Posted to France in 1915, he witnessed the rise in horrific facial wounds caused by the combination of heavy artillery and trench warfare, with soldiers peering over the parapets.

This led Gillies to set up a multi-disciplinary team of surgeons, nurses and artists at Queen Mary’s Hospital. Antibiotics were not yet available, so successful reconstructive surgery was very difficult due to the risk of infection. Gillies and his team attempted ground-breaking procedures using grafted flaps of skin and transplanted bone ribs. Gillies famously invented the ‘tubed pedicle’, a technique that used a flap of skin from the chest or forehead and swung it into place over the face. The flap remained attached but was stitched into a tube. This kept the original blood supply intact and dramatically reduced the infection rate. These surgical techniques are documented in the case files and photographs in the collection.

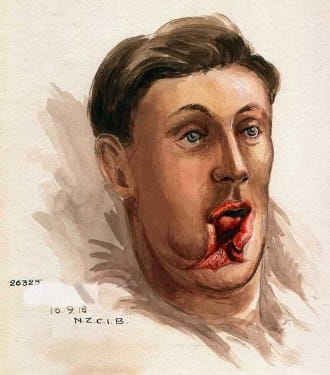

Above: watercolour portraits showing a soldier before and after facial reconstruction surgery performed by Harold Gillies and his team in 1918-1920 (artist unknown).

Gillies focussed on both functionality and aesthetics. Mindful of the social stigma of facial disfigurement, he tried to make patients similar to how they looked before their injury. He used the black and white photographs to record his patients’ injuries and plan their repair. The photographs show the initial injury, most often to the jaw or nose, and the outcome of surgeries.

Queen's Hospital patients of this era were almost exclusively servicemen. Most were soldiers, with a small number of Navy and Flying Corps personnel, most of whom had suffered burns. The records include rank, number, regiment and date of wounding so that the action in which they were wounded can often be identified.

Gillies sometimes called upon artists to paint colour portraits of the wounded soldiers and take casts of their faces. Among them was Henry Tonks FRCS, who trained as a surgeon before he became a professional painter. Some water colours are in the archive collection while Tonks’ pastel portraits and some of the casts are preserved in the RCSEng Hunterian Museum collection.

Like the film 1917, this collection commemorates the soldiers of the First World War. The case files have inspired some researchers to trace the lives of the soldiers and tell their individual stories.

Victoria Rea, Archives Manager