The Great History Bake Off: Baking and Medicine in Early Modern Recipe Books

21 Oct 2016

Ginny Dawe-Woodings

Above: A medieval baker with his apprentice (public domain image from Wikimedia Commons).

The act of baking has developed from a fundamental staple cooking technique to the artistic and creative activity we know today. Since August, we have been engrossed in the Great British Bake Off (GBBO), and it has inspired us to examine the recipe books held in the archives at the College in search of interesting historical bakes.

Many of the foods which we enjoy today have their origins in the medical world. Tonic water was developed by adding quinine (an anti-malarial medication) and sugar to water as a prophylactic against malaria in 19th century colonial India. Cornflakes were created in 1894 by Dr Harvey Kellogg as a health food, and chocolate has been used for millennia to treat (not always successfully) everything from angina and asthma to snakebites and syphilis. The recipe books in the Archives are excellent examples of the historical cross-overs between medicine and cooking.

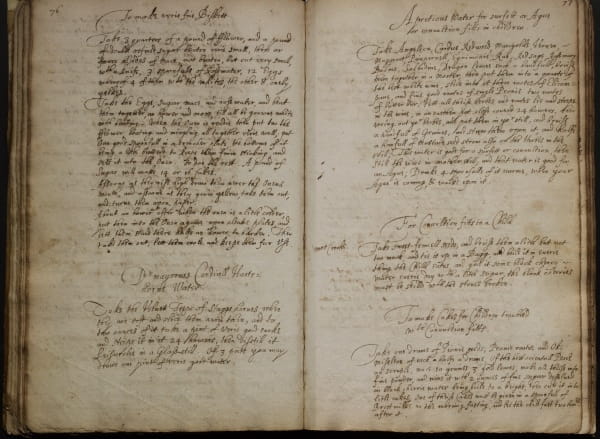

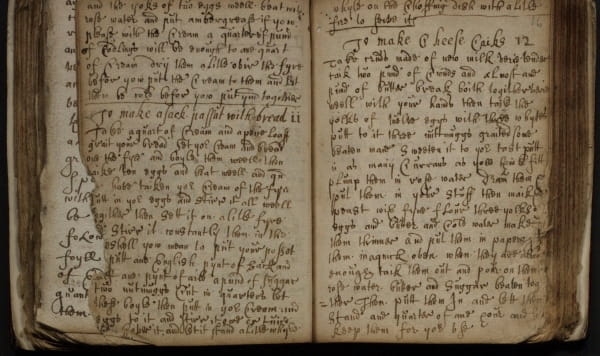

MS0059 is a book of handwritten recipes compiled by Sydney Humphryes (written c1646-c1668) which brings together medicine and baking; containing recipes for specific medical ailments, recipes for delicious sounding baked goods, and recipes which are a bit of both. The recipes are written in an unfamiliar style which list the ingredients and method separately, and instead resemble something that Mary Berry and Paul Hollywood might suggest for the “technical challenge” on GBBO. Only a very small amount of the recipes have specific quantities for ingredients, and even fewer have cooking times or temperatures, instead referring to “quick” or “brisk” fires and relying exclusively on the colour of the bakes to determine whether it is cooked or not – as you can see in the biscuit recipe above. Humphryes’s recipe book does not separate out what is medicinal and what is “just baking”, the recipes for sherbet lemon and biscuits sit happily beside recipes for cordials to cure dropsy and syrups and jelly pastels for a cold.

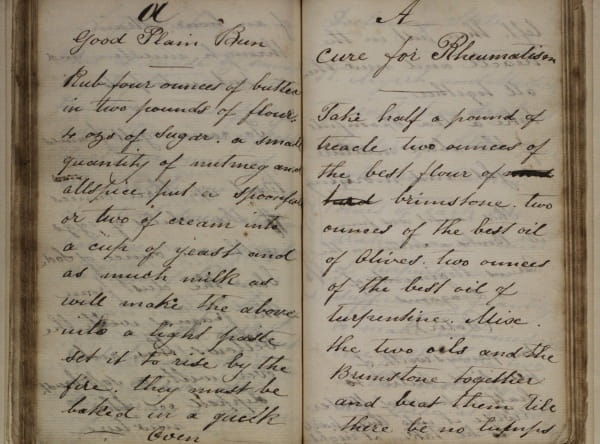

This process of compiling medicinal and culinary recipes together is also found in J Sharp’s late-18th Century manuscript, where a recipe for a “good plain bun” sits next to a recipe for a “cure for Rheumatism”.

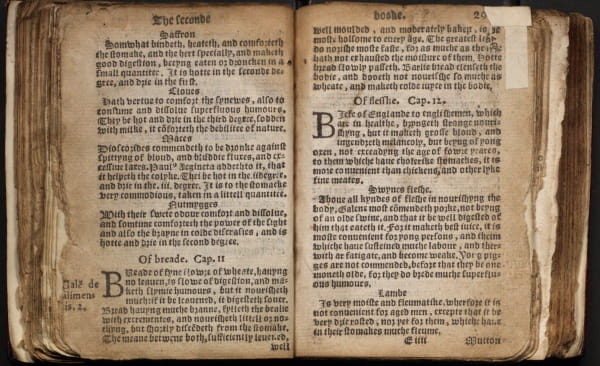

The recipe books in the Archives date from the 17th through to the 19th Centuries. In the early part of this era diets were still largely governed by Galen’s (129-216AD) ideas on balancing the humors of the body, and consequently cookery books were occupied with determining the specific humoral qualities of food and their preparation – this process was called “tempering”. As seen in manuscript MS0475, the author outlines the effects of bread on the digestive system and the humors, explaining that bread “havyng no leaven, is slow of digestion, and maketh slymie humours, but it nourisheth much…Barlie bread clenseth the bodie, and dooeth not nourishe so much as wheate, and maketh colde juyce in the bodie”. Another section details the effects other food stuffs have on the humors: apples, cucumbers and medlars are cold and moist, but rosemary, ginger and walnuts are hot and dry. This section of printed text called “The Complexion of Man” was bound into a recipe book which features recipes for “Lemmon Caiks”, “whyt syllabub”, “Cheese Caiks” and “makarounds” (macaroons), implying that the author was probably concerned with the impact that baking could have on their humoral balance. Perhaps they could introduce a Renaissance week to GBBO where contestants are expected to balance Paul’s choleric humors? Luckily towards the end of the volume, after all the mentions of cakes and sugar, there is also a recipe for tooth ache and “an excellent diet drink” which contained ivory, sarsaparilla, white poppies, raisins, dates, and ale.

The content and time span covered by the recipe books makes them a great resource for studying both food and medical history, and the wonderful and occasionally appetising ways that they overlap.

Recipe Transcription from Sydney Humphryes’s recipe book

Modern Recipe “to make verie fine Biskett”

Ingredients:

- ¾ lb or 340 g Flour

- 1 lb or 450 g Sugar

- 8 Egg yolks

- 4 Egg whites

- 1 tsp Ground Mace or 4 Mace strands

- 2 tbsp rosewater

Method:

Preheat oven to 180° C. Grease and line a baking tray. Beat the eggs, sugar, mace, and rosewater together in a bowl until light and fluffy, and then add the flower until well combined. Spoon the mixture onto the baking tray and place into the oven. Once risen, turn the oven down to 150° C and bake until they are golden brown. Turn the oven down to 120° C and bake until hard, and serve. This recipe should make 14-16 biscuits.

Ginny Dawe-Woodings, Museums & Archives Project Cataloguer