The Twelve Days of Christmas Part - 2

11 Dec 2015

Collections Review Team

Last week Part 1 of our Twelve Days of Christmas series brought us a partridge in a pickle-jar, a rather nice illustration of a turtle dove, a manuscript from the archives about a hen’s egg and some interesting and very different larynges to represent our calling birds. This week we look at Days 5-8 with some more fascinating books, manuscripts, and items from the museum collections.

Five Gold Rings

The College holds numerous gold medals, five of which are shown here. Three of them show an image of a snake, a traditional Greek symbol of healing.

The first from the left (RCSSC/M 96) is the gold medal of the Lyceum Medicum Londinense, a society set up by John Hunter and his friend Dr George Fordyce in 1785 to encourage medical research.

The second (RCSSC/M 15) is a replica of the Royal Society of Medicine gold medal (offered since 1920) and depicts a mythical creature (the centaur Chiron) teaching the young Asclepius.

The third (RCSSC/M 84) is the honorary medal of the Royal College of Surgeons, first awarded in 1802 for distinguished work towards the improvement of the healing art. It shows Galen finding a human skeleton, a scene which first appeared in William Cheselden's Osteographia of 1733.

The penultimate medal (RCSSC/M 13) is the Fothergill medal of the Medical Society of London, presented to Leonard Colebrook in 1944. Colebrook (1883-1967), a pioneer in therapeutics and patient safety, campaigned for the use of gloves and gowns during the treatment of patients and introduced the use of antibacterial drugs (prontosil and then sulphonamides) for the treatment of puerperal sepsis.

The final item (RCSSC/M 85) is the Linnean Society Medal, featuring a portrait of Carl Linnaeus by William Wyon, chief engraver at the Royal Mint. The Linnean Society was founded in 1788 and is the world's oldest active organisation devoted exclusively to natural history in the broadest sense. This example was presented to Sir H G Howse, President of the College 1901-1903.

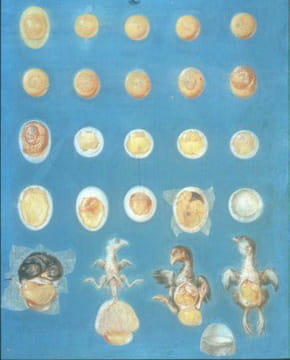

This composite pastel drawing by Jan van Rymsdyk (1758-9) shows a series of developing eggs. It was commissioned by John Hunter to show the development of chicken and geese embryos as part of his investigations into products of generation and animal reproduction. More images of the Museum’s visual works can be seen in a The Chicken or The Egg Art Lectures on the RCS library blog.

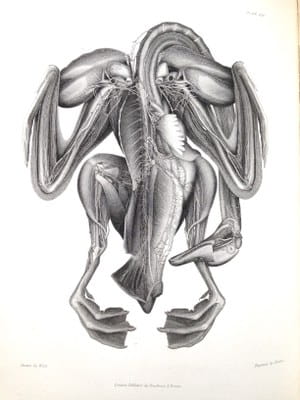

This item is more of a double-Swan than seven of them. The striking plate is from Joseph Swan’s Illustrations of the Comparative Anatomy of the Nervous System (1864) and shows a swan’s nervous system. Swan (the man, not the animal, 1791-1874) was one of the College’s original 300 Fellows. Although he stopped practicing surgery early on in his career, he was a master dissector and anatomist, and published a number of works on the nervous system throughout his life. Around three dozen specimens prepared by him remain in the Hunterian Museum’s collection today.

Eight Maids a-Milking

Our example for maids-a-milking illustrates one the most important medical discoveries in the world!

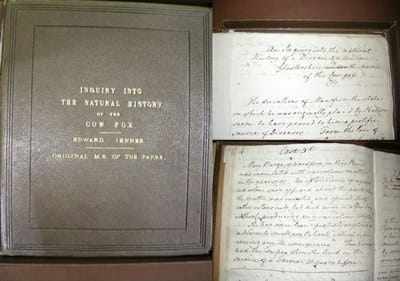

Milkmaids were sometimes infected with cowpox, caught from the cows they were milking. Cowpox was a mild viral infection of cows that caused weeping spots, or pocks, on their udders. When milkmaids caught cowpox they were a little unwell for a few days and sometimes developed some pocks, often on the hands. Edward Jenner had heard stories of how people who had caught cowpox would not go on to develop smallpox, a deadly disease caused by the variola virus which killed between 10-20% of the population. Jenner was interested in these stories of cowpox preventing smallpox, and was able to undertake an experiment to test if the story was true.

Jenner published his research in 1798; an early example of tried and tested research based on observation and experimentation. In the College collections, we hold a manuscript draft copy of his publication (MS0016/1), as well as the published version An inquiry into the causes and effects of the variolæ vaccinæ; a Disease Discovered in some of the Western Counties of England, Particularly Gloucestershire, and Known by the Name of The Cow Pox (1798).

Look out for our forthcoming exhibition on Vaccination in spring 2016 at the Hunterian Museum!

Collections Review Team